Part 1. The Mind in Motion: Evolution, Cognition, and the Future of Thought

To change the way we think, first change the way we feel. Kevin Rigley

The Evolution of Cognition

When did humans first become aware of their own thoughts?

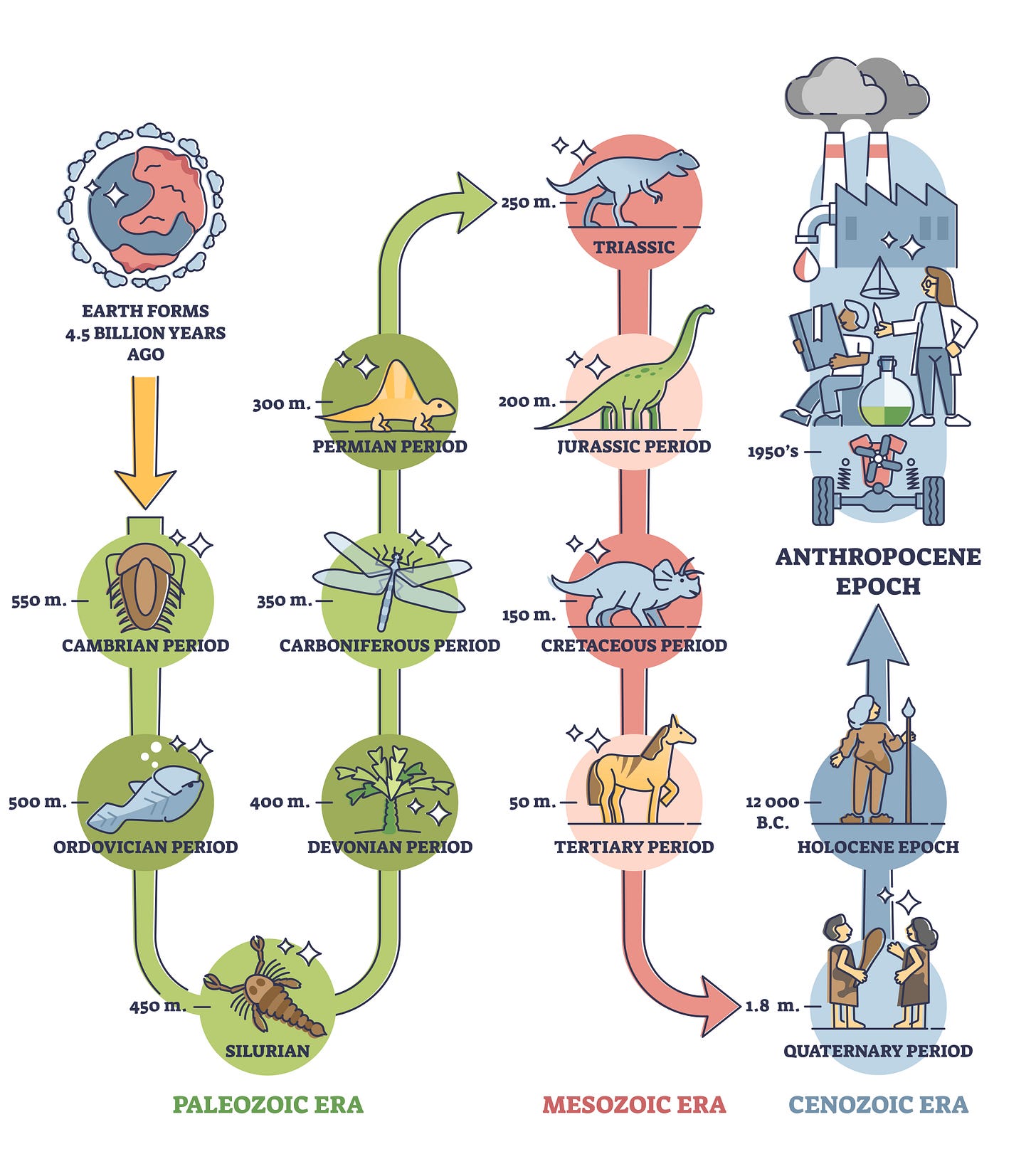

Throughout most of evolutionary history, cognition was primarily reactive. Early organisms were unaware and responded to environmental stimuli solely through instinctual behaviours. As nervous systems evolved, many cognitive processes remained subconscious, driven by survival instincts. A crucial shift occurred when thoughts transformed from simple reactions into conscious awareness. This marked the emergence of conscious cognition, a significant milestone in the development of intelligence. With conscious thought, humans developed the ability to not only respond but also to reflect, anticipate, and modify their actions. This capability to observe one’s thoughts, recall past experiences, and envision future scenarios laid the foundation for problem-solving, creativity, and complex social interactions.

What triggered this transformation? Some theories propose that increasing social complexity created selection pressures favouring individuals with enhanced cognitive abilities. In early human societies, the capacity to anticipate actions, comprehend intentions, and navigate social dynamics likely provided a survival advantage. Others argue that language and storytelling were crucial, boosting self-awareness by enabling people to articulate, share, and refine their experiences. An alternative perspective suggests that environmental uncertainty favoured adaptable thinkers who could respond swiftly to changes. Regardless of the origins, one fact remains clear: conscious awareness transformed everything.

Despite its significance, a considerable portion of our cognition remains beyond our direct control. Although thoughts appear to arise spontaneously, they actually follow organised neural and environmental patterns, surfacing from subconscious processes before we become aware of them. This raises a crucial question: Is thinking a product of free will, or are we merely choosing from pre-existing options? If thoughts emerge without intentional effort, it suggests that cognition may operate more like a biologically regulated system, akin to how the body manages other functions such as temperature, blood sugar, or immune responses.

Crucially, in the theory of evolution, the environment selects phenotypes that will thrive. This offers a vital clue: all neurotypes depend on the environment in which they develop. Just as different physical traits confer advantages in specific ecological conditions, various cognitive styles may be more or less adaptive depending on environmental demands. If environmental pressures shape cognition, then perhaps conditions like ADHD, ASD, and anxiety are not deviations from the norm but rather natural cognitive adaptations to different environmental requirements. This perspective shifts the focus from individual traits to the interaction between cognition and the environment, challenging the notion that any neurotype is inherently superior.

This article examines the idea that thought generation and awareness function as stable equilibria in biological systems influenced by principles similar to various homeostatic processes in the body. Just as metabolism and immune responses maintain equilibrium, cognition may depend on the interplay between subconscious thought generation and conscious thought selection. When this equilibrium shifts, different cognitive states can emerge.

Rather than viewing ADHD, ASD, and anxiety as “dysregulated” conditions or natural variations, they may be understood as distinct cognitive equilibria shaped by environmental inputs. Recognising that cognition exists in multiple stable states allows for a broader perspective on neurodiversity, shifting away from deficit-based models toward an understanding of adaptive variation.

The Subconscious as an Autonomic Process

“What if your subconscious is not just in your brain, but part of your nervous system?”

Many individuals perceive their subconscious as an abstract concept, a hidden mental process distinct from bodily functions. But what if the subconscious is closely integrated with the body? What if it operates like heart rate, digestion, or breathing—overseen by the autonomic nervous system (ANS) rather than being merely a function of the brain? This viewpoint challenges the traditional understanding of thought as a voluntary process. Just as you do not consciously regulate your heart rate, most thoughts emerge without direct control. Yet, they are not random; they follow structured patterns shaped by both internal physical conditions and external environmental factors. The ANS, which aids in maintaining homeostasis, may also influence and filter subconscious thoughts.

The Autonomic Nervous System (ANS) is comprised of two primary branches. The Sympathetic Nervous System (SNS), often referred to as the “fight-or-flight” system, facilitates arousal, alertness, and rapid behavioural responses. It prepares the body for immediate action and may also contribute to quick thought generation, problem-solving, and impulsivity. In contrast, the Parasympathetic Nervous System (PNS), known as the “rest-and-digest” system, promotes calmness, concentration, and contemplation. From a cognitive standpoint, it may oversee thought selection, filtering, and sustained focus on a single idea. If the subconscious operates within the ANS, this suggests that the processes of thought generation and selection are biologically driven rather than merely voluntary. The brain continually oscillates between phases of rapid thought production (SNS) and deliberate thought selection (PNS), akin to how the body balances activity with rest. Unlike functions such as heart rate or digestion, the conscious mind can engage with this process—choosing, refining, or even redirecting thoughts as they emerge.

Just as external stimuli can influence heart rate, environmental factors also play a significant role in determining which thoughts rise to the forefront of our consciousness and which remain in the subconscious. A high-stress environment may activate the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), resulting in an increase in thought generation but a decline in cognitive control. Conversely, a tranquil environment can enhance parasympathetic nervous system (PNS) activity, fostering greater focus and deliberate thought selection. If we think of the subconscious as a calculator, the autonomic nervous system (ANS) governs which calculations occur in the background. In stressful states, it prioritises survival-oriented thinking, while in relaxed moments, it promotes deep reflection and effective problem-solving. This suggests that cognition is not solely driven from within; it is shaped by biological regulation and the surrounding environment. If the ANS influences how thoughts arise and are selected, variations in cognitive styles—such as those observed in ADHD, ASD, or anxiety—may be viewed as different expressions of how autonomic balance affects cognition.

If the subconscious operates as an autonomic process, we need to rethink the concept of free will in cognition. Choosing thoughts involves more than merely “trying harder” or applying willpower; it’s a biological process influenced by autonomic balance and environmental factors. The upcoming section examines how these subconscious mechanisms establish unique cognitive equilibria, affecting how various individuals perceive and engage with their surroundings.

Two Levels of Conscious Awareness

“Do you choose your thoughts, or do they choose you? Does Free Will Exist?”

For centuries, philosophers and scientists have debated the nature of free will. Are our decisions truly conscious, or do we simply execute predetermined calculations beyond our awareness? In the 1980s, neuroscientist Benjamin Libet aimed to address this issue with a pioneering experiment that has become a cornerstone in the discussion of human cognition. His results questioned traditional views on free will, implying that our brains might make decisions prior to our conscious awareness.

Libet’s experiment featured a straightforward design but carried significant implications. Participants were asked to flex their wrist while observing a quickly moving clock to identify the exact moment they became aware of their intention to move. Their brain activity was recorded via EEG during this task. The hypothesis was that brain activity would start either simultaneously with the moment participants recognized their decision or shortly after. However, the findings were surprising: brain activity, referred to as the readiness potential (RP), commenced almost 500 milliseconds before the participants consciously decided to move. This indicated that the brain had already begun the movement process prior to the participant’s awareness of their choice to act.

This discovery led many to conclude that free will is an illusion. If decisions occur subconsciously before we are consciously aware of them, our perceived control may be illusory. Nonetheless, Libet himself hesitated to embrace a deterministic view fully. He suggested a middle ground: although we may not consciously initiate our actions, we might possess a “veto” function—the capacity to inhibit subconscious decisions before they are executed. This concept, known as “free won’t,” implies that while our decisions may not stem from conscious intent, we can still act to halt specific actions. However, subsequent research indicates that even this veto function may operate unconsciously, further questioning the significance of conscious thought in our decision-making processes.

If all thoughts and choices stem from the subconscious, what role does free will play? Rather than rejecting free will outright, I suggest a broader perspective. Let’s consider cognition as functioning on two levels of awareness. The first is Level 1 Awareness (Reactive Thinking), where thoughts arise spontaneously. Subconscious processes, past experiences, instincts, and environmental triggers shape these thoughts. In this phase, people passively experience thoughts as they come, without critically analysing them. In contrast, the second level—Level 2 Awareness (Critical Thinking & Cognitive Control)—involves active engagement. Here, individuals do more than notice thoughts; they intentionally refine, assess, and guide their thinking.

Libet’s findings, rather than disproving free will, provide evidence for a two-tiered model of cognition. The subconscious generates thoughts and impulses and reports them to the conscious mind. At Level 1, the thoughts are noted, while Level 2 allows for intentional reflection and modification. This reframes free will not as the power to create thoughts but as the ability to engage with and shape them intelligently. Free will is not about initiating thoughts from nothing but about selecting, refining, and influencing the ones that arise.

Cognitive Flexibility and Environmental Inputs

To better understand this, consider the calculator-director analogy. The subconscious functions like a calculator, constantly running computations and generating potential thoughts. Level 1 Awareness is like an observer, passively noticing the calculator’s output but not engaging with it. Level 2 Awareness, in contrast, acts as a director, actively selecting which problems the calculator should solve, refining its inputs, and modifying its outputs. Libet’s research supports this model: our thoughts emerge before we are aware of them, but that does not mean we lack control over them. Consciousness does not create thoughts—it directs them.

This perspective also offers insight into why some individuals struggle with cognitive control. The ability to move from Level 1 to Level 2 Awareness depends on autonomic nervous system (ANS) flexibility, which regulates the balance between the sympathetic nervous system (SNS), responsible for rapid, instinctive thinking, and the parasympathetic nervous system (PNS), which supports reflection and cognitive regulation. When ANS flexibility is low, individuals may struggle to override automatic thoughts, keeping them trapped in reactive thinking. Conversely, those with high ANS flexibility can transition between reaction and reflection, allowing for greater cognitive control. This may explain why individuals with ADHD often experience an overwhelming influx of thoughts that make selective attention difficult, while those on the autism spectrum tend to hyperfocus on specific thought patterns, restricting cognitive flexibility. Anxiety, too, can be understood through this model: negative thoughts dominate Level 2, reinforcing cycles of worry and hypervigilance. Rather than viewing these as disorders, they may represent stable cognitive equilibria—different ways in which individuals experience and manage thought selection.

If Level 2 Awareness depends on autonomic flexibility, then training the ANS could enhance cognitive control. Activities that improve ANS adaptability include meditation, structured play, cognitive training, breathwork, and physical movement—all of which have been shown to strengthen attention, executive control, and cognitive flexibility. Developing a strong Level 2 Awareness is not simply a matter of effort but of creating the right physiological conditions for higher-order cognition to thrive.

Libet’s research revealed that we do not initiate thoughts from scratch, but this does not mean free will is an illusion. Instead, free will operates at Level 2 Awareness, where we engage with, refine, and direct the flow of our thoughts. The real question is not whether we control the origin of our thoughts, but whether we actively shape their trajectory. Rather than asking, “Do I have free will?” the more accurate question is, “How well am I directing my thoughts?”

Ultimately, the shift from passive thought reception to intentional thought selection is the key to developing higher-order cognitive control. This shift can be strengthened with training, awareness, and environmental design. You are not the source of your thoughts. You are the director of their refinement.

Click for Part 1

Click for Part 2

Click for Part 3